Recently, the period in which Ukrainian cities had to complete the renaming of Russian and imperial toponyms has expired. A new wave of changes in toponyms was caused by the beginning of the full-scale invasion. Since then, decolonization had been voluntary, and after the adoption of the new law, it has become mandatory.

The Transparent Cities program has been researching for 2 years the achievements of Ukrainian cities in removing toponym names that were imposed on us from urban our space. Our analysis covered 83 cities in Ukraine.

During this time, we recorded both active renaming and blatant stalling and sabotage of this process. Although the initiative in renaming has already passed from cities to regional state administrations (which currently have the status of RMAs), some municipalities continue the decolonization.

Current statistics

7,800 toponyms were renamed, starting from March 2022 to May 2024, in 83 cities under study. At least 650 more are subject to change. Some cities state that they have completed the derussification processes. These are Vinnytsia, Drohobych, Dunaivtsi, Mukachevo, Ternopil, and Khmelnytskyi.

The ten cities where the highest number of toponyms was renamed within two years include:

- Kryvyi Rih

- Kharkiv

- Dnipro

- Kyiv

- Zaporizhzhia

- Vinnytsia

- Kramatorsk (city military administration)

- Kamianske

- Poltava

- Odesa

The number of renamed toponyms does not always indicate the qualitative progress of the city. Some city councils in the west of the country now have insignificant quantitative indicators in decolonization because they actually started this process at the time of the restoration of Ukrainian statehood.

In the study, we focused on the renaming of urbanonyms (intracity topographic objects). The change of names concerned streets, squares, lanes, avenues, parks, as well as districts in cities, metro stations, public transport stops, railway stations. The names of libraries, schools, kindergartens, memorial complexes, and rehabilitation centers were also changed. In Lozova, the center for comprehensive rehabilitation for persons with disabilities was renamed The Shining of Life instead of The Pearl (tr. note—this word was used in Russian). The Pervomaisk-na-Buzi railway station got its historical name restored—Holta. In Kalush, the kindergarten Cheburashka (tr. note—a Soviet cartoon character) became Kobzaryk (tr. note—the diminutive form of a Kobza player).

Certain cities, in addition to renaming toponyms, bring the existing ones to the standards of the state language. For example, in Kamianske, Moldavska Street became Moldovska Street, Ovrazhna Street became Yaruzhna Street, and Richna Street became Richkova Street.

Some city councils provide information about the renamed toponyms in a separate section on their official website so that citizens can quickly review the new names. For example, lists of renamed toponyms were developed in Dnipro, Kyiv, Kropyvnytskyi, Lubny, Oleksandria, or Okhtyrka. Kyiv City Council has developed a separate dashboard containing information about the engagement of citizens in the change of toponym names. Sumy City Council, in addition to aggregated provision of information, also creates short introductory videos about new toponym names.

Our analysts did not consider the renaming of settlements, which takes place in Ukraine partly because of the need to adapt them to the standards of the Ukrainian language or remove the symbols of the imperial policy. We are talking about Novomoskovsk, Pervomaisk, Yuzhnoukrainsk, Pavlohrad, Sievierodonetsk, Chervonohrad and Yuzhne. The fact is that although such a decision is adopted after preliminary consultation between local authorities and the public, it is the parliament that is responsible for it. The specialized committee of the Verkhovna Rada has already supported the renaming of a number of settlements. In total, more than 300 settlements in Ukraine need their names changed.

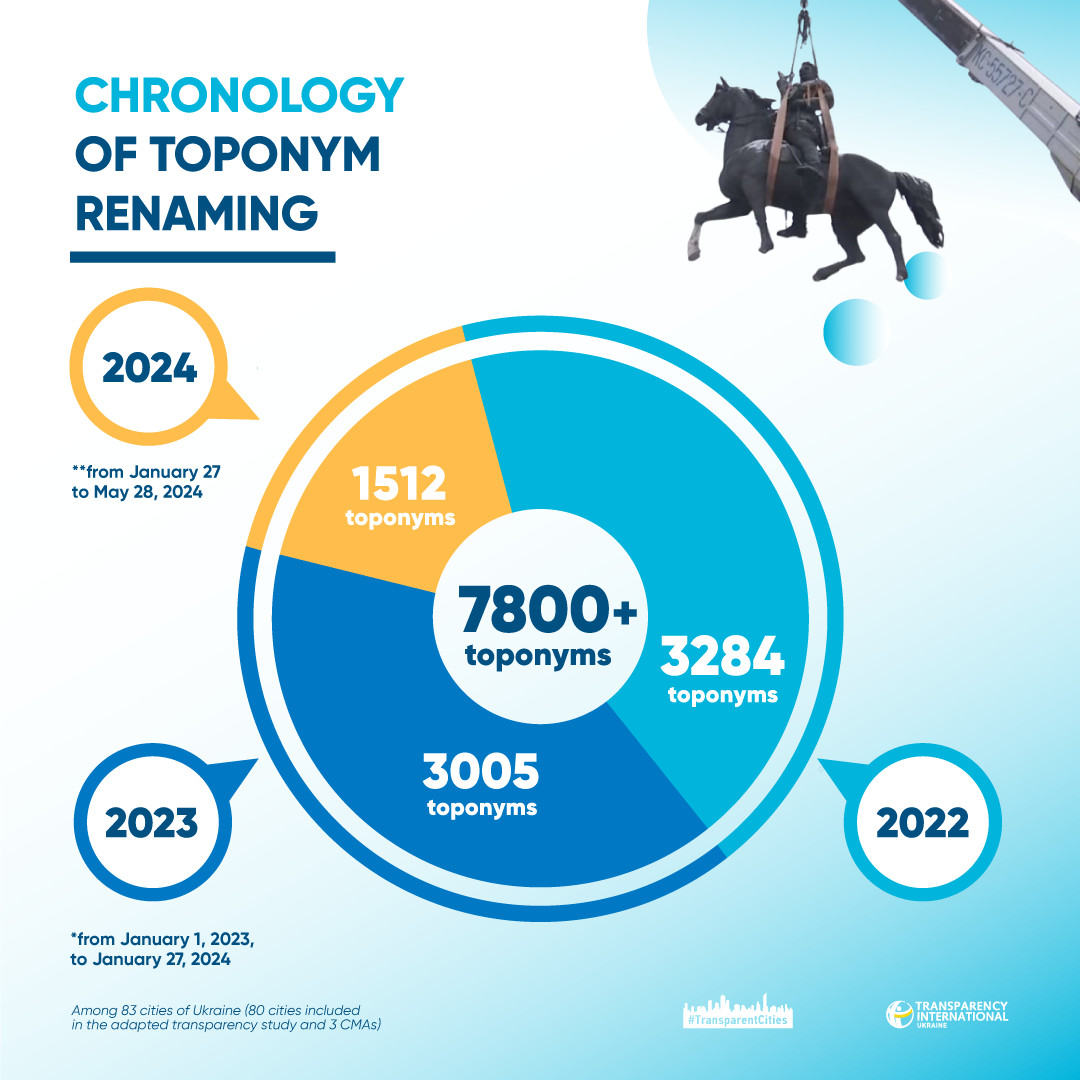

The analysis of the decolonization processes strongly suggested that they had occurred in a wave-like manner. The 80 cities under study renamed the highest number of toponyms in 2022—3,284, which is 42% of the total number of the names changed. That year, decolonization was voluntary, stemming from the desire to get rid of the symbols we shared with the empire given the brutal full-scale invasion by Russia.

NB! Although the Law of Ukraine on Condemnation and Prohibition of Propaganda of Russian Imperial Policy in Ukraine and Decolonization of Toponymy entered into force on July 27, 2023, the processes of renaming had had been completely legitimate before that. According to Anton Drobovych, head of the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory, local authorities had all the legislative powers to rename toponyms and dismantle monuments. The important thing was to adopt appropriate decisions regulating the procedure or to follow the existing procedures.

In 2023, fewer toponyms were renamed in cities—about 3,000. This was often due to the fact that the main array of toponym names had been changed in the previous year, and it took time for the toponymic commissions to develop a new one. Moreover, some cities had completed the decolonization process back in 2022, and some municipalities stalled it.

Between late January and mid-May 2024 (when the renaming became the responsibility of the mayor until the last measurement of the program on May 28), more than 1,500 toponyms were decolonized. This is almost half of the toponym names renamed last year. The program assumes that the cities were so active in order to fulfill the requirements of the specialized law (spoiler alert—they failed).

Most of the toponyms were voluntarily renamed by Kyiv, Vinnytsia, Sumy, Kramatorsk, and Kremenchuk. Since the legislation came into force, the following cities have been included in the list of renaming leaders:

Among these cities were those that had been engaged in decolonization before they were forced to do so by law, in particular Dnipro and Kryvyi Rih. According to our observations, some cities renamed most of the toponyms in the last days of the statutory terms. Thus, Kharkiv mayor Ihor Terekhov issued an order to rename 387 toponymic objects on April 26. A similar situation was recorded in Pavlohrad and Odesa, where the orders of the mayors were dated April 23 and 24, respectively.

Decolonization issues: the stances of the authorities, the public, and the Transparent Cities program

The process of renaming, like any process that entails a change in meanings and symbols, had its difficulties. Both city councils and residents faced them. Municipalities note that the key problems during the decolonization of toponyms for them were the following:

- Criticism of both the process itself and the new names. Citizens oppose renaming because they believe it entails amending all title documents after changing the names of streets or lanes. In its guide, he program explained in detail why this fear was unfounded. In addition, for some citizens, decolonization is unimportant and irrelevant. For example, in Konotop, residents sent a collective appeal to ban the renaming of streets and lanes in the city. Citizens criticize the options proposed by the authorities, but they themselves choose not to come up with new names (Lozova criticized the process of renaming, but only 23 appeals with proposals were received).

- The need for clarification from specialized institutions(the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory, the Ministry of Culture and Information Policy) on whether the name is subject to the law on the de-Russification of toponymy.

- Prolonged search for new names or discussion of certain options. In Chernihiv, residents opposed the name Chortoryskyi Yar instead of Dekabrystiv. After long discussions, the street was renamed Sviatomykhailivska.

- The desire of residents to use depersonalized names, such as Kvitkova (Flower), Chepurna (Elegant), Yaskrava (Bright) streets. Decolonization, on the other hand, aims not only to abandon imperial markers, but also to create new social patterns.

The public, in its communication, also expresses comments on how the renaming of urbanonyms took place. These include:

- Lack of proper dialogue between the authorities and the community or representatives of the renaming commissions. In Kryvyi Rih, members of the city toponymic commission were not informed why the city council had removed 82 names from the preliminary list of the regional working group.

- Illogical choice of names or reasons for decolonization. For example, the renaming of Metalists Street in Kyiv caused the lack of understanding among urbanists. Or why the historical name of Sakharov Street in Ivano-Frankivsk was changed (Ukrainian political prisonersof Soviet times opposed it). In Konotop, September 6 Street was named after the director of the Ostrava municipal enterprise, which provided Konotop with 10 buses. The citizens believe that the name of the street was “bought.”

- Neutral names or assigning significant names to objects on the outskirts of cities.The public was outraged by the fact that in Horishni Plavni, toponyms associated with Pushkin, Chkalov, and Gagarin were assigned neutral “plant” names, in particular Lypova (lime tree), Kashtanova (chestnut tree), and Lozova (vine plant) streets. Meanwhile, in Odesa, small or remote streets were renamed in honor of the dead soldiers.

- Limited time for public discussion of new names. For example, in Kyiv, only 5 days were given to choose new names for 237 toponyms. According to public observations, the most popular names were those that came first in the proposed list.

Analysts of the program also recorded that some municipalities deliberately or not renamed toponyms slowly. In Zhmerynka, a year passed between surveying citizens and renaming toponyms, although the current legislation provides that consultations cannot last more than 30 calendar days. In Mykolaiv, decolonization got rolling only this spring. The head of the toponymic commission explained that the delay was caused not only by disputes over new names, but also by the lack of a quorum at almost every second meeting.

What will happen with decolonization?

The provision of the law on decolonization obliged local governments to rename toponyms that contain the symbols of the Russian imperial policy within six months from the date of entry into force of the law, that is, from July 27, 2023.

Unless the local authorities adopted a decision before the above-mentioned date, the village or settlement head, a city mayor had another three months to adopt such an order.

After that, and until July 27, 2024, such a decision is made by the head of the relevant regional state administration (currently regional military administration) or a person who, in accordance with the law, exercises their powers for the next 3 months, namely, until the end of July 2024.

However, the process of renaming in municipalities continues even after the deadline. Last week, the city councils of Zaporizhzhia and Uzhhorod decolonized the names of dozens of streets. Why is this happening, and is it lawful?

Such actions by local authorities are lawful. A number of current provisions1 stipulate that the preparation and submission for consideration of issues related to the naming (renaming) of streets, lanes, avenues, squares, parks, public gardens, bridges, and other structures located on the territory of the relevant settlement shall be under the jurisdiction of city councils. In addition, renaming city districts and assigning the names of individuals, anniversaries, and festive days to legal entities and objects of ownership are carried out, in particular by the city council or the military administration of the settlement.

“In addition to these legislative acts, in practice, most local councils have provisions approved by them and not canceled in court on the procedure for renaming toponymic objects in the territory of these settlements. They regulate in detail their actions when changing toponym names. So, if a local council makes a decision on renaming now, there is no reason to say that it was made unlawfully,” says Anna Kuts, legal advisor to TI Ukraine.

In any case, the toponyms associated with Russia or its imperial heritage will still be renamed, not by the RMAs, but by local self-governments. The most important thing is not to stall this process and finally remove markers of Russian identity from our space.

How we conducted the research

Analysts of the Transparent Cities program analyzed the decolonization of toponym names in 83 cities in 23 regions of Ukraine in the period from March 2022 to May 28, 2024.2 These are 80 cities of the adapted study of transparency in cities and 3 city military administrations (Pokrovsk, Kramatorsk, and Kherson), whose experience the program studied in the past years. As a basis for the analysis, we took data from open sources (official websites of city councils; Facebook pages; Telegram channels of local self-government bodies, the mayor, or their deputies; the media), as well as the answers of city councils to official requests related to toponym renaming.

The program analyzed the change in toponyms within the city, without considering information on starosta districts that are part of the territorial community. The program did not study the renaming of the settlements.

1The provisions of the Laws of Ukraine on the Procedure for Solving Certain Issues of the Administrative and Territorial Structure of Ukraine, on Local Self-Government in Ukraine, on Assigning the Names (Pseudonyms) of Individuals, Anniversary and Holiday Dates, Names and Dates of Historical Events to Legal Entities and Objects of Ownership

2The first stage of data updating took place between April 20 and May 15, 2024. However, between data updates and the publication of this material, six cities additionally derussified about 200 toponyms. To make the data more relevant, the program considered these changes and reflected them in the total number of renamed toponyms. At the time of publication of the material, the data were relevant as of May 28.