The Transparent Cities program examined how the mayors of Ukraine’s 100 largest cities1 reported on their work in 2024. Seventy mayors published activity reports, but only 24 of them responded to questions from the public2.

According to the Law of Ukraine on Local Self-Government, mayors are required to report to their communities twice a year. However, current legislation does not set out a clear procedure or any liability for failing to report or for doing so in a purely formal manner. In practice, most mayors simply publish an annual summary report on the city council’s website.

Mayoral accountability in 2024

Last year, analysts from the program assessed how the mayors of 80 cities reported to the public. In 2023, 51 communities had an opportunity to hear a report from their mayor, yet announcements about the reporting events were published in only 20 cities.

Among the 77 mayors whose accountability was assessed two years in a row, a degree of progress is evident: in 2024, seven more mayors submitted reports than the year before. In 2023, 49 mayors from this sample reported to their communities; in 2024, the number rose to 56.

Of Ukraine’s 100 largest cities, 70 mayors published reports for the previous year (as of 1 July 2025). Nineteen of these were published at the end of 2024, while 51 appeared during the first half of 2025. This means that 30 community leaders violated the law by failing to inform residents about their activities.

Only in 33 cities was it possible to find video recordings of public reporting events, either held as separate events or during city council sessions. In other cases, mayors either published a written report on the city council’s website or failed to provide any video confirmation of such events. Only 30 city councils announced their reporting events in advance, and residents were able to ask the mayor questions in just 24 out of 100 communities, as evidenced by video recordings or official news reports accompanying the events.

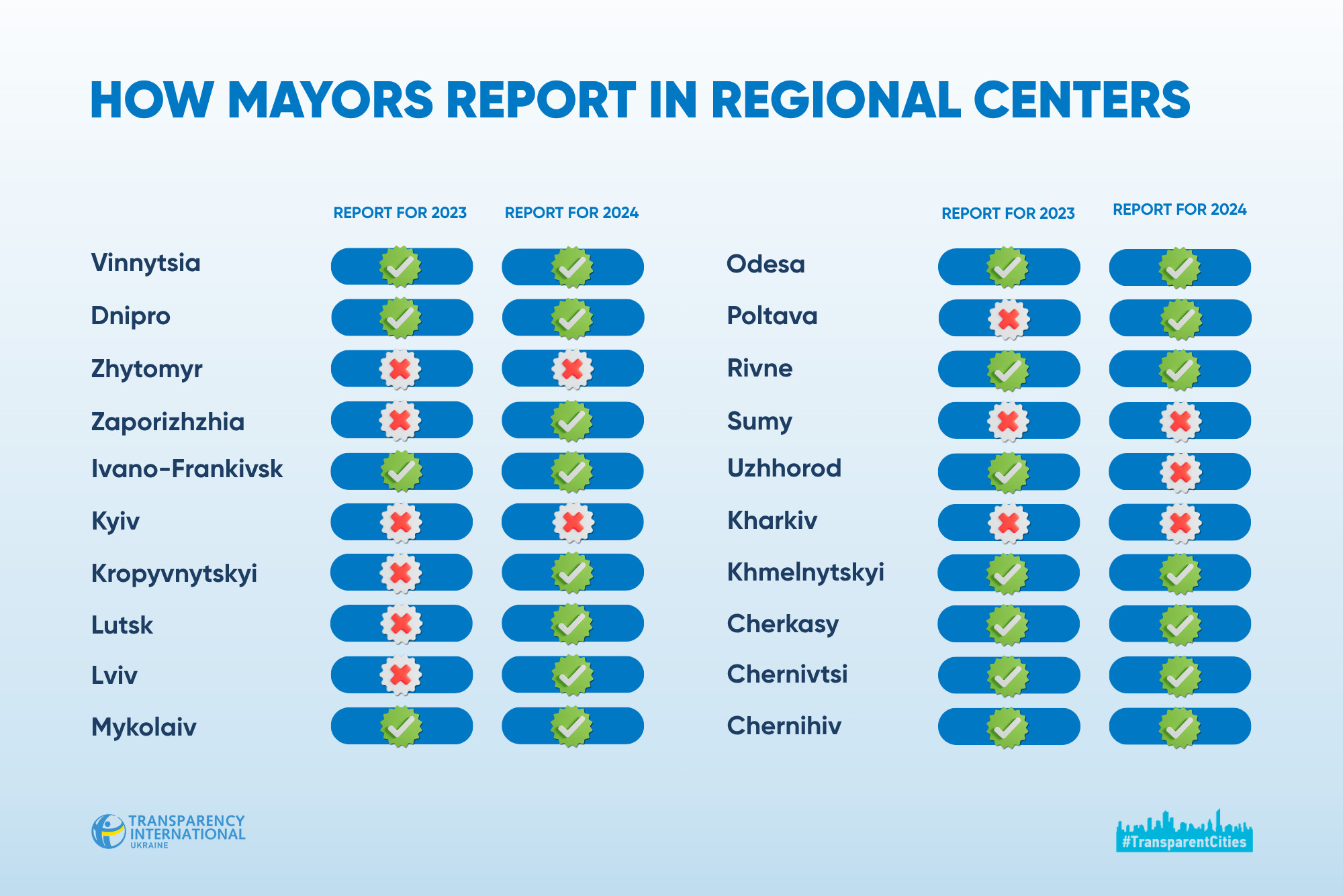

Among the 20 regional centers studied, mayors in 15 cities submitted reports. The mayors of Kyiv, Sumy, Uzhhorod, Zhytomyr, and Kharkiv failed to report at all. Ten regional leaders delivered public reports accompanied by a video recording or livestream, while public participation (the ability to ask the mayor questions was documented in six cities: Dnipro, Ivano-Frankivsk, Lutsk, Poltava, Rivne, and Chernivtsi. In some cities, representatives of the Armed Forces and members of the public were invited to deliver short speeches during open events — for example, in Odesa. However, analysts note that such involvement can hardly be considered meaningful public participation, as the speakers are usually pre-selected individuals giving mostly complimentary remarks, while ordinary residents are not given the opportunity to raise issues that genuinely concern the community. The mayors of Khmelnytskyi and Cherkasy limited their reporting to appearances on local TV channels, which also deprived residents of the chance to engage in direct dialogue with local authorities.

Unfortunately, the mayor of the capital also failed to set a positive example. Only scattered updates on individual areas of activity were made public, rather than a comprehensive report.

Cities in the Kyiv region showed the weakest performance among all regions: out of 12 communities in the Kyiv region, only four mayors — those of Bila Tserkva, Boiarka, Brovary, and Pereiaslav — submitted reports. Video recordings of reporting events were published in Bila Tserkva and Pereiaslav, but these events were not properly announced in advance. In Boiarka, the opposite was true: the report was announced, but no video was published. None of the four cities documented any questions from the public.

No mayor among the cities analyzed in Zakarpattia (Berehove, Mukachevo, Uzhhorod, Khust), Kirovohrad (Kropyvnytskyi, Oleksandriia, Svitlovodsk), or Kharkiv (Zlatopil, Lozova, Kharkiv) regions held a public reporting event for 2024 — or at least no videos, announcements, or news posts about such events were found. In some cases, only a written version of the report was published on official websites.

Among the ten cities located in potential hostilities, mayors in seven published reports on their 2024 activities. The mayors of Marhanets, Sumy, and Kharkiv failed to publish end-of-year reports.

Out of the 100 communities assessed, only 13 fully complied with best transparency practices: announcing the reporting event in advance through public channels, ensuring resident engagement and participation, providing a livestream and video recording of the event, and publishing a detailed written report. Among the successful examples are four large cities: Lutsk, Rivne, Poltava, and Chernivtsi; four medium-sized cities: Drohobych, Kolomyia, Stryi, and Uman; and five small towns: Boryslav, Brody, Volodymyr, Zviahel, and Chortkiv.

These results demonstrate that high-quality reporting is not exclusive to large cities or regional centers. For example, mayors in both the regional center of Lutsk and the significantly smaller town of Volodymyr met all the reporting criteria. One-third of the top performers are small and medium-sized cities in the Lviv region, where mayors not only report publicly but also respond to residents’ questions. In contrast, no questions from residents were recorded in the video of the Lviv mayor’s report. Moreover, he only resumed the reporting practice in 2025, following a pause that lasted since 2022.

Successful reporting practices among mayors of small towns

Of the 24 cities where mayors responded to questions from the public, 10 were small towns (with populations under 50,000), seven were medium-sized, and six were large cities, including three regional centers. Among the small towns whose mayors answered questions openly were three communities in Lviv region (Boryslav, Brody, and Novoiavorivsk); two in Volyn region (Volodymyr and Novovolynsk); and one each in Zhytomyr region (Zviahel), Rivne region (Dubno), Poltava region (Myrhorod), Sumy region (Okhtyrka), and Ternopil region (Chortkiv).

This distribution confirms once again that being a small town does not mean lacking capacity. On the contrary, when there is political will, small municipalities can often adopt changes more quickly and engage the public more effectively thanks to closer ties between residents and local authorities.

For example, despite the difficult security situation, the mayor of Okhtyrka held a public report in late 2024 at the local Culture and Leisure Center. Although no video was published, news reports confirmed the participation of over 150 residents, who raised questions on healthcare, public infrastructure, and environmental issues.

In Brody, the mayor also held an open reporting event in April 2025, covering the city council’s work in 2024. The event took place at city hall, was announced in advance via the council’s official social media, and gathered residents who asked questions about local roads, housing for military personnel, recreational zones, and other topics.

In Zviahel, a public event was held in January 2025 and was announced in advance through official communication channels. Residents were offered several convenient ways to submit questions for the mayor: via an online form, email, comments under Facebook posts, or by calling a dedicated hotline. Questions were also asked live during the event.

These examples demonstrate that even under resource constraints and external challenges, mayors can maintain direct communication with citizens. A public report doesn’t have to be a large-scale event in a packed auditorium — it just needs to be an honest conversation in an accessible format, with the opportunity to ask questions both in person and online.

Overall, the study shows that mayors are more inclined to publish polished summaries of the past year’s successes than to engage in honest discussions about the difficult issues facing their communities. Because the law does not specify when or how mayors must report, each official chooses the format most convenient for them.

The Transparent Cities program recommends that mayors follow a few key principles:

- Announce the report: whether it’s a dedicated event or part of a city council session, the report should be announced at least one business day in advance. If the report is part of a council session, it's best to publish not only the draft agenda but also a separate announcement about the report. The announcement should be shared across various public channels to reach a broad audience.

- A defining element of openness is the ability of residents to ask questions —either during the event or remotely. Online forms, hotlines, or comments under livestreams on social media can all be used. This two-way communication turns reporting into a real tool for public oversight and civic influence.

- A written version of the report and a video recording of the event should always be made public. Ideally, videos should be uploaded to the city council’s official website or YouTube channel, since Facebook only stores livestreams for 30 days. This will ensure the publicity of information and equal access to it for all who are interested.

The Transparent Cities Program strongly advocates for open dialogue between authorities and communities. A mayor’s report should not be a formality — it should be a chance to communicate the municipality’s work across all areas, and an opportunity to receive feedback that helps set priorities, allocate resources more effectively, and build public trust.

At the same time, the Law on Local Self-Government should be amended to establish clear timelines and reporting formats, account for martial law conditions, and introduce accountability for violations. This would prevent mayors who exploit legal loopholes from avoiding their duty to report and engage with the public — those who elected them in the first place.

1 The sample included the 100 largest cities in Ukraine, according to data from a mobile operator, with the exception of Ternopil, which was excluded from the study due to documented cases of data falsification on the city council’s official website.

2 Analysts assessed whether at least one report for 2024 had been published (either in late 2024 or in 2025). They checked for the presence of a written report on the official website and whether a public reporting event had taken place. They also noted whether the event was announced at least one business day in advance, whether a video or livestream was available, and whether the public had a chance to ask the mayor questions.

*Analysts assessed whether at least one report for 2024 had been published (either in late 2024 or in 2025). They checked for the presence of a written report on the official website and whether a public reporting event had taken place. They also noted whether the event was announced at least one business day in advance, whether a video or livestream was available, and whether the public had a chance to ask the mayor questions.