Russia’s war has caused enormous damage to Ukraine’s infrastructure. In some places, entire towns and villages have been destroyed. After the victory, one of the main challenges for Ukraine will be reconstruction. After all, our main task is not only to rebuild what was destroyed, but also to make it “better than it was.”

The team of Transparent Cities (Transparency International Ukraine) continues to share the world’s experience in rebuilding cities. This is useful for Ukraine, as history has already collected unique concepts of recovery, typical mistakes, and ways to solve them. Next in line is a story about the rebuilding of Tokyo, which has experienced several disasters in less than 20 years.

The Historical Aspect

During its existence, the Japanese capital has twice suffered colossal destruction. The city was almost completely destroyed. Firstly, the reason was natural disaster, then — war. As a result, the modern look of Tokyo is absolutely different from the city that existed more than 100 years ago.

Since the Japanese archipelago located on the seismic belt, the country is occasionally “shaken.” But the Kantō earthquake of 1923 was unique in its strength and caused the greatest destruction in Japanese history. The aftershocks, along with tsunamis, gas pipe explosions, and power short circuits, caused massive destruction and fires in two Japanese cities, Tokyo and Yokohama. The capital lost a third of its buildings, and 45% of the city's territory was in ruins.

Destroyed Tokyo after the 1923 earthquake © rarehistoricalphotos.com

Destroyed Tokyo after the 1923 earthquake © rarehistoricalphotos.com

Reconstruction began with the creation of master plans and concepts. Former official Goto Shimpei saw the earthquake devastation as a unique opportunity to rebuild the real Tokyo and relieve the city's dense development. He proposed a grandiose reconstruction plan, which was implemented partially due to a lack of financial resources and resistance from political elites and residents. The central part of the city, instead of the former solid neighborhoods, received a convenient street system, parks and squares, public spaces, and new bridges. However, Tokyo did not exist in this form for long.

Bombed Tokyo in 1945 © U.S. National archives

Bombed Tokyo in 1945 © U.S. National archives

At the end of World War II, the Americans bombed to smithereens the capital and other Japanese cities, which was then Hitler's ally. Fighters dropped tons of bombs on the city (only on February 25, 1945, 453 tons of incendiary bombs were used). The constant air raids continued until Japan announced its surrender in August 1945. The bombing killed 100,000 civilians, destroyed more than 250,000 buildings, and severely damaged industrial facilities. More than 28% of the Tokyo metropolitan area was devastated.

Tokyo Recovery Plans

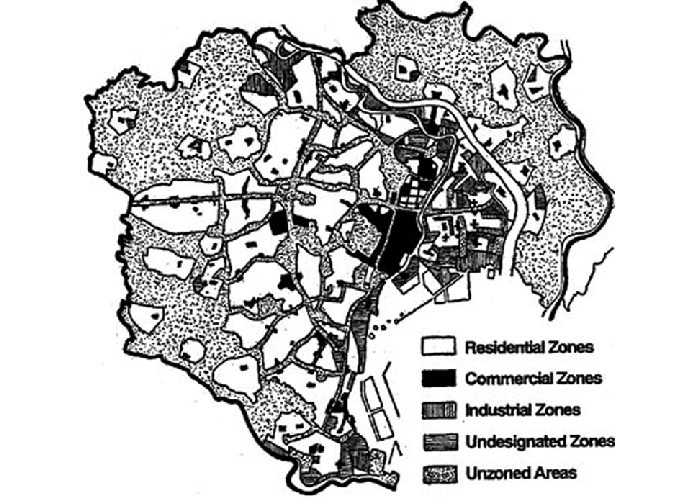

This time, more cities had to be rebuilt. In addition to Tokyo, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Yokohama, Nagoya, Toyama, and other cities were burned and destroyed. The Recovery Plan developed for Tokyo largely followed the previous vision of rebuilding the city that existed after the earthquake. The author, Ishikawa Hideaki, formed it in 1946 based on European experience and previous Japanese achievements. He sought to decentralize Tokyo and divide it into smaller districts of 300,000 of inhabitants. It was planned to create parks and 100-meter-wide boulevards with promenades between the districts. The districts, each to become a mini-center within Tokyo, were to be connected by highways. The total area for the city's redevelopment was 200 km².

Plan for the restoration of central Tokyo in 1946 © Tokyo Metropolitan Government

Plan for the restoration of central Tokyo in 1946 © Tokyo Metropolitan Government

To convince Tokyo residents of the need for a complete rebuild, the city government even created a promotional film “Tokyo in 20 Years.” However, an acute lack of funds “buried” this plan at the beginning of the work. The area to be restored was reduced to 50 km², of which only 15 km² were completed.

Urbanists Matthias Ekhanove and Rahul Srivastava are convinced that the failure to implement the Recovery Plan gave the city a chance to recover differently, but still quickly and efficiently.

How did the Postwar Reconstruction Proceed?

Ishikawa's ideas were not forgotten — the overall vision of Tokyo as a “city of villages” with small district centers was implemented without a master plan. The authorities decided that the city should be rebuilt by the residents.

Indeed, residents of Tokyo's neighborhoods were allowed to decide for themselves which objects they would rebuild, which they would not, and where they would build a green park. The city authorities focused on creating infrastructure, and most of the work on rebuilding housing was done directly by Tokyo residents, who reconstructed their city meter by meter, remembering what it looked like before the destruction.

Tokyo street in the evening © Wikipedia

Tokyo street in the evening © Wikipedia

The city also decided to reduce the scale of architectural projects. Record-breaking skyscrapers, showy giant projects, and unique tourist locations are great for cities on a global scale, but not for residents. That is why the Tokyo authorities have focused on creating micro spaces where people can do their own thing with little or no money. In an alleyway, on a comfortable park bench, under a bridge — wherever possible, Tokyo tried to create convenient locations for people.

Japanese journalist Robert Whiting wrote: “In 1959, when Tokyo won the bid to host the Olympic Games, the capital looked nothing like the gleaming high-tech metropolis it would later become. It was an ugly sprawl of old wooden houses, empty shacks, cheaply built plaster houses, and danchi.” For reference, danchi is the Japanese equivalent of cheap and simple housing, comparable to the massive “Khrushchev” in the USSR.

A construction boom and favorable conditions from the government launched a rapid recovery process. By 1955, the city was already home to 7 million people, and the agglomeration's population grew from 5 million to more than 20 million in 10 years. By the 1970s, Japan had managed to increase its housing stock by 65%.

Gradually, the authorities allowed the construction of taller and taller buildings as the need for housing, offices, and commercial space grew. The city has only recently become as tall as it is now. For example, 70% of the city's skyscrapers were built after 2000, and in the last century, most buildings outside the business center of Tokyo were lower than 10 floors.

Tokyo skyscrapers © muza-chan.net

Tokyo skyscrapers © muza-chan.net

In 20 years, the government and private developers have built 10,000 new office and residential buildings with a height of 4–7 floors, 100 km of new highways worth USD 55 mln, 40 km of subway lines, and the Shinkansen bullet train between Tokyo and Osaka. Transport in the city can be reported functions according to the clock — citizens trust the subway schedules so much that they set alarms for the time of arrival at the desired station and can afford to take a nap in the car.

In Tokyo, people do not need cars because every neighborhood can be reached by public transport. It accounts for more than 50% of urban transportation. In addition, Tokyo's neighborhoods are so multifunctional that they have all the infrastructure and entertainment you need.

High-speed train Sinkansen © iStock.com/Yongyuan Dai

The number of unique establishments in Tokyo is impressive — there are dozens of cafés and small shops on almost every street. That became possible because the authorities allowed residents with two- or three-story apartments to open small businesses on the ground floors.

Today, about 37 million people live in Greater Tokyo together. This is slightly less than the population of the whole of Ukraine! In the city, slums and skyscrapers, old wooden buildings, and new concrete ones coexist side by side. It seems that Tokyo is a complete mess, but in fact, the combination of disorder and order is a distinctive feature of the Japanese capital.

Why is Tokyo an Irregular City?

Japanese architect Kisho Kurokawa says that Japanese culture recognizes that disorder and order are inseparable. To understand the mentality in the city, it is worth evaluating Tokyo as an open and receptive, flexible metropolis.

And the prominent architect Arata Isozaki suggests that the Japanese do not perceive the city as a collective cultural product because Tokyo was completely destroyed in 1945, and most people grew up during the years of rapid urban growth in an environment where there were no old buildings. The culture of disaster and reconstruction changed the way Tokyo residents viewed their city. The citizens allowed a new city to emerge organically in place of the old one.

View of Tokyo from the Tokyo Skytree observation deck in 2019 © REUTERS/Issei Kato

Therefore, there are almost no historical buildings in Tokyo, and in this respect, the city differs from, for example, Kyoto, where control over the preservation of cultural heritage is very strict. Kyoto was much better preserved during the Second World War because it was removed from the list of targets for bombing and replaced with the city of Nagasaki as a target for dropping the atomic bomb.

Lessons for Ukraine

- Engage residents in the reconstruction process. It is possible to conduct surveys, organize exhibitions, or even invite people to participate directly in the development of ideas and construction.

- Preserve the cultural heritage. It is necessary to care for the history of the city so that it has its own identity in the future.

- Create sustainable neighborhoods and unite the community so that in case of emergencies, we can respond to threats faster. Read more about how to build strong communities in cities in Victoria Onyshchenko’s column on Khmarochos.

- Allow business to build and make this process organized and transparent. This way, we can avoid uncontrolled development and the prevalence of commercial interests over comfort for all city residents.