Ukraine's European integration path is irreversible. This is evidenced by the state’s concrete commitments, the consistent position of European partners, and stable public support — 74% of citizens favor EU membership (according to TI Ukraine). But European integration is not only about the national-level state policies. It is also implemented through decisions made locally in communities and cities, where, in particular, the standards of good governance, transparency, and citizen engagement are implemented.

For that reason, the Transparent Cities program studies to what extent Ukrainian cities are prepared for the EU integration in those matters. As part of the pilot format of our research, analysts evaluated the openness of municipalities based on European approaches.

The assessment criteria align with the requirements and recommendations of key documents — the Council of Europe’s Principles of Democratic Governance, the Ukraine Facility Plan, the European Commission’s Enlargement Package Reports for 2023–2024, among others. For the category on openness and public engagement, the priorities reflect the requirements of the Ukraine Facility Plan, particularly the provisions related to decentralization and regional policy, and the reform “Strengthening tools for citizen participation in local-level decision-making.” The assessment also incorporates provisions concerning civil-society participation in the architecture of investment and recovery processes. Evaluation approaches are harmonized with European methodologies, including the EU public-sector digital transformation monitoring method set out in the eGovernment Benchmark 2025.

Openness of city councils and their interaction with communities is the corner stone of any democratic governance. Before turning to advanced digital solutions or other best local practices, it is crucial to understand whether cities ensure basic openness — whether an ordinary resident can, with minimal effort, find information about the full cycle of decision-making and implementation in the community. Cities must proactively inform citizens and engage them in co-creation of urban life.

For the purposes of this study, openness is understood as the completeness, relevance, accuracy, and structured nature of public information on the activities of local self-government bodies, aligned with the broader European approach to developing e-governance (the Europe's Digital Decade 20 initiative). Reflecting this orientation toward European practices, analysts measured the practical openness of official city-council resources, applying, among other things, the “single entry point” principle. They also examined dimensions of openness specific to the Ukrainian context but crucial for maintaining the support of European partners — transparency in managing humanitarian aid, coordination of recovery and reconstruction, and inclusive engagement of citizens from various regions and social groups.

Research methodology

The methodology of the European Cities Index (the Euroindex) provides for a shift from one-off annual measurements to continuous monitoring. Analysts will record changes in transparency and accountability of city councils several times a year. That will be a step-by-step research with thematic blocs — openness of city councils, e-services, open data, use of budget funds, prevention of corruption, and so on. Each step will be supported by a separate methodology, with simultaneous announcement of results.

Analysts collected data in September 2025. They checked whether the information is relevant for the whole 2025, except for several indicators, where the 2024 data was included as well (regulatory activities, comprehensive programs for defenders, etc.). The pilot sample included 10 regional centers (Dnipro, Zaporizhzhia, Kropyvnytskyi, Lutsk, Lviv, Odesa, Poltava, Kharkiv, Khmelnytskyi, Chernihiv) and the city of Kyiv. Pre-selected cities of various transparency levels represent all Ukrainian macro-regions and war contexts (rear cities, cities included in the List of Territories of Potential Hostilities).

Openness and public engagement were assessed through 40 indicators. Analysts checked published information about the meetings of city councils, their executive committees, and selected standing committees. In this part, they considered only the meetings of the council and its bodies held in the second quarter of 2025. They also analyzed the publication of key strategic documents of the council, the functionality of website search tools, and accessibility for users with visual impairments, and the availability of complete, up-to-date, and accurate information on regulatory policy, management of humanitarian aid, compensation for damaged or destroyed property, and information for vulnerable population groups.

Important: The assessment required the presence of stable thematic sections/pages where all relevant reference information is collected and continuously updated, as well as correct links to internal and external documents/resources.

How well do major cities meet European standards of openness?

When assessing openness and public engagement in Ukrainian cities, analysts relied on the premise that genuine transparency does not begin with merely formal disclosure, but with the logic, completeness, and accessibility of information for residents. If a citizen can find the necessary information in just a few clicks — whether on council meetings, regulatory policy, recovery efforts, or humanitarian assistance — this signals a certain level of institutional maturity.

The study covered two key dimensions: openness (availability and relevance of information) and public engagement (accessibility and structure of information, communication with residents, inclusiveness during times of crisis). The program’s experts aimed to identify and describe the barriers to practical access to essential information and to verify whether Ukrainian cities are moving toward European standards of digital governance.

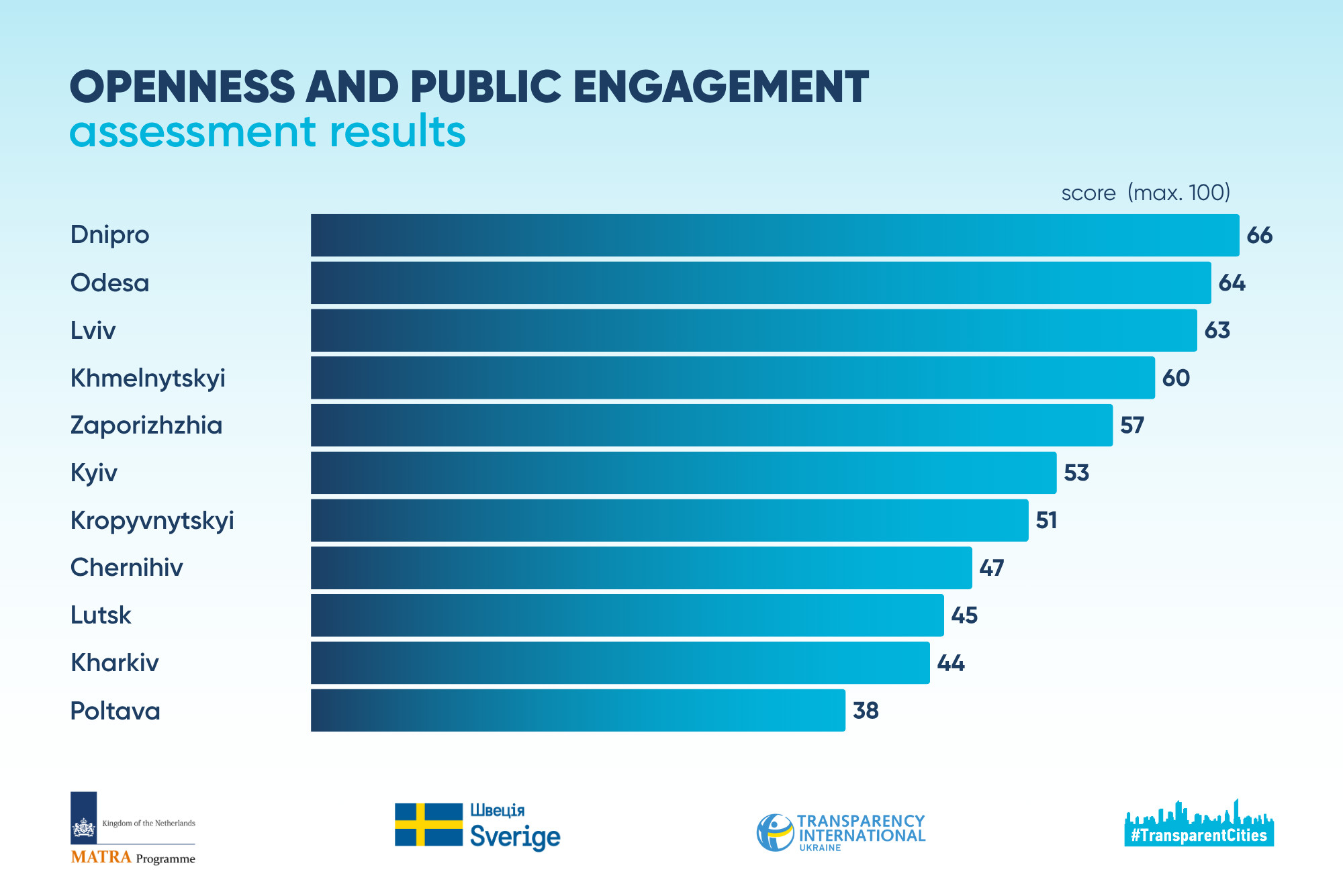

The average performance across the 40 indicators of Openness and Public Engagement is 53.5%.

Dnipro achieved the highest result — 66 out of 100 points. One position lower is Odesa with 64 points, followed by Lviv with 63 points. The lowest results were recorded in Poltava (38), Kharkiv (44), and Lutsk (45). Kyiv ranked in the middle of the sample with 53 points.

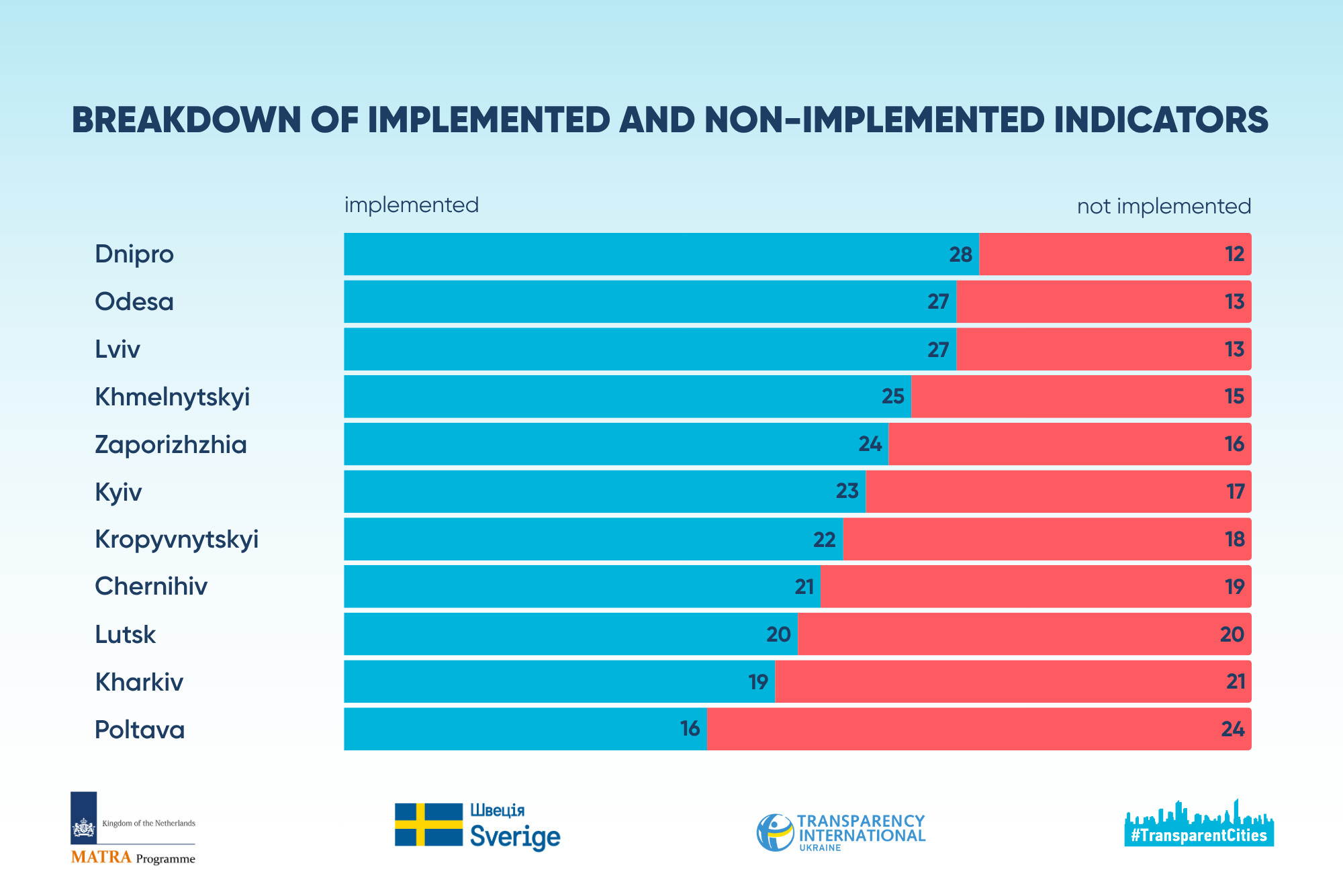

Dnipro and Lviv demonstrated consistency in their approaches. In the Openness and Public Engagement categories of the 2024 Transparency Ranking, both cities were among the top ten: Dnipro implemented 93.1% of indicators in these areas, while Lviv achieved 87.5%. This year, both regional centers also showed strong results: Dnipro met 28 out of 40 indicators (the highest score in the sample), and Lviv — 27.

Odesa succeeded in improving its performance compared to the 2024 Ranking, where the implementation level for these categories stood at 58.3%. In this year’s pilot assessment, the city implemented 27 indicators, matching Lviv.

Lutsk, by contrast, ranked among the top five cities in 2024 with an implementation level of 91.7% in openness and public engagement. However, during this year’s assessment, the city met 20 out of 40 indicators. The most significant challenge was a set of six indicators related to the announcement of meetings of the city council, executive committee, and standing committees — criteria that were refined to match European standards.

In 2024, Poltava implemented 51.4% of the indicators in these categories — the lowest result among the cities in the sample — and again demonstrated the weakest performance in this study, implementing only 16 indicators.

Two cities with the status of territories of potential hostilities — Kharkiv and Zaporizhzhia — took part in the study. Despite facing similar challenges, these regional centers performed differently in meeting openness requirements. Zaporizhzhia implemented 24 indicators, while Kharkiv met 19. These results are consistent with the performance of frontline cities in the 2024 assessment.

Overall, all analyzed cities demonstrated fairly average results. Even those that outperformed others did not exceed two-thirds of the maximum possible score, indicating substantial room for improvement.

Strengths and weaknesses

All cities included in the study publish decisions of the city council and executive committee, as well as orders issued by the mayor. All 11 cities also arranged livestreamed council sessions in the second quarter of 2025 (detailed recommendations on appropriate broadcasting formats are available in the program’s extended analytics). Performance was weaker when it came to broadcasting meetings of the executive committee — only seven cities ensured livestreams, while Kyiv, Lviv, Kharkiv, and Chernihiv did not provide broadcasts of all meetings. Lutsk was the only city that did not publish all recordings of meetings of the designated standing committees.

Regulatory policy also proved to be an area with relatively strong results. Nine cities properly published their Plans for Preparing Draft Regulatory Acts of the City Council and Executive Committee, and eight published structured links to the regulatory acts themselves.

None of the cities in the sample published aggregated, structured statistics on decisions regarding compensation for damaged or destroyed real estate in a dedicated section. Analysts examined whether cities disclosed consolidated figures on the number of decisions granting compensation, the number of approvals and refusals, and the total amounts disbursed. Some information is available — for example, the final paragraphs of Lviv’s commission minutes contain the number of adopted decisions, while Odesa provides information on the number of decisions, refusals, approvals, and suspended reviews. However, no city published data on the total amount of compensation paid. The only city that ensured the presence of commission documents on compensation within the relevant section was Chernihiv.

Another highly problematic area was the publication of information on the management of humanitarian aid. All 11 cities failed the corresponding indicators. Eight cities did not even create a dedicated section on this topic. The absence of a structured section on humanitarian-aid management during a full-scale invasion is a critical shortcoming, and the program has previously issued recommendations on this matter — which remain relevant. In Dnipro, Kyiv, and Chernihiv, where at least thematic sections existed, the required information (the Procedure for receiving and distributing humanitarian aid and the List of Recipients among city-council subordinate entities) was not added.

European approach to information publication

Program experts examined whether Ukrainian municipalities adhere to Europe-wide governance approaches in their handling of public information. An essential element of these approaches is the “single entry point” principle. This requires that city-council websites maintain convenient, regularly updated thematic sections containing all necessary information and correct links to documents and resources. The principle is aligned with the European practices discussed further.

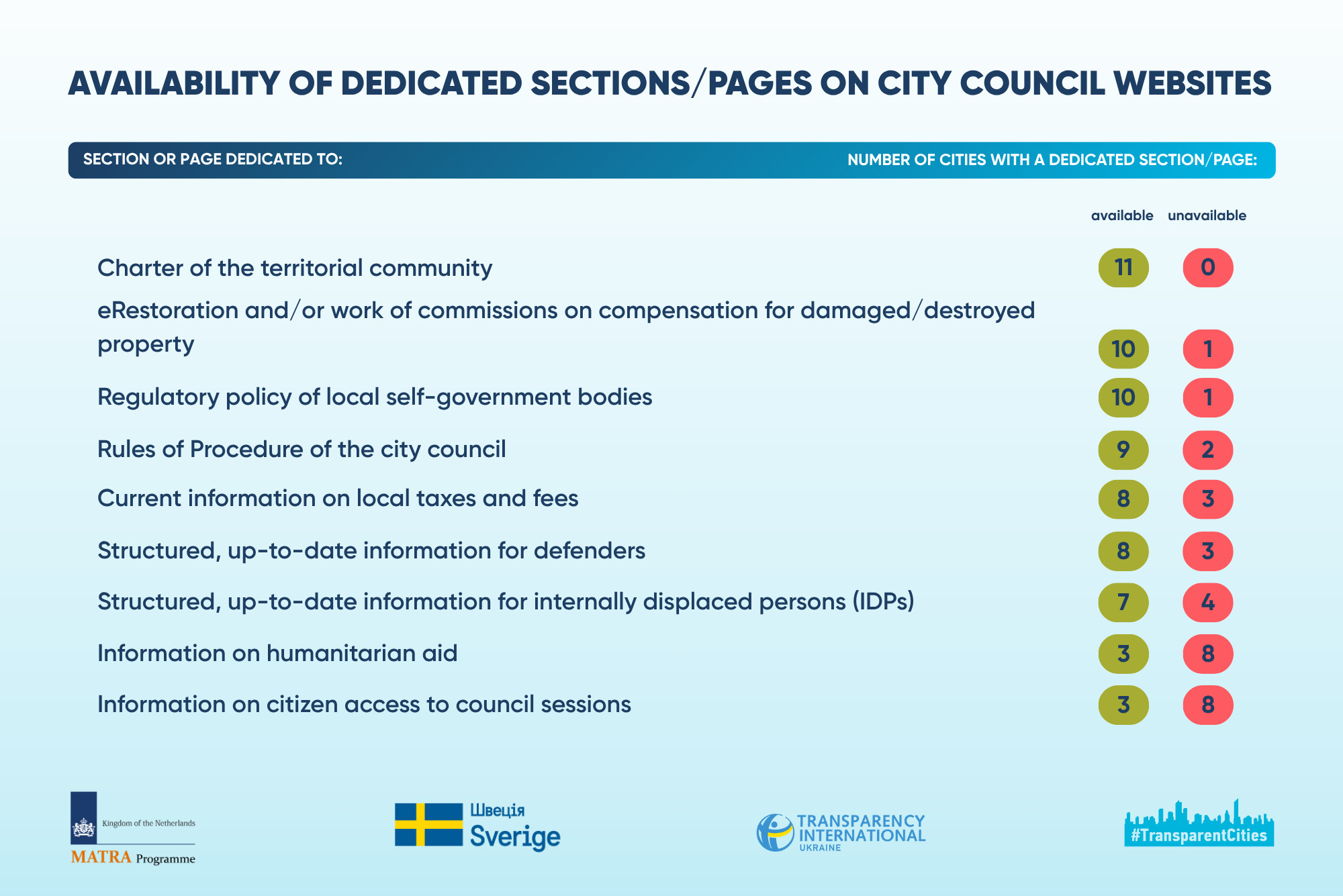

The "single entry point" principle was assessed across nine topics. Analysts searched for dedicated sections or pages on the Charter of the territorial community; the Rules of Procedure of the city council; regulatory activity of local self-government bodies; local taxes and fees; citizen access to council sessions; the eRestoration program and the work of compensation commissions for damaged/destroyed property; humanitarian aid; information for defenders; information for internally displaced persons (IDPs).

The only city that met this principle fully was Kyiv. Lviv came close: its official website contains thematic pages for eight of the nine required topics, lacking only a page dedicated to humanitarian aid. The websites of these cities display a high level of openness and an effort to build meaningful public engagement through logical and user-friendly structuring of information.

All 11 cities had a dedicated page for the Charter of the territorial community. A complete, up-to-date, approved version of the Charter was available in 10 cities. A best practice is to specify the exact dates of amendments and provide links to the corresponding decisions, as implemented in Kyiv. Only in Kharkiv was the Charter outdated on the dedicated page (although analysts found a decision on amendments that had not been reflected there).

Most regional centers (10 out of 11) ensured the availability of unified pages on eRestoration and compensation processes, as well as on regulatory policy. Kropyvnytskyi offered a well-organized regulatory-policy section with clear subsections for reporting, planning, performance evaluation, etc. The website of Khmelnytskyi did not include a dedicated section on eRestoration, while Poltava lacked a page on regulatory policy. Both cities were in the process of transitioning to updated website versions during the assessment. Analysts evaluated the current state at the time, but this transition offers Poltava and Khmelnytskyi a favorable opportunity to incorporate program recommendations into the structure of their new websites.

The most problematic topics — absent as unified sections in eight cities — were humanitarian aid and citizen access to council sessions. A dedicated page outlining the algorithm for accessing council sessions is a prerequisite for a straightforward path from a citizen’s intention to attend a meeting to the practical ability to do so. Program analysts have detailed what proper disclosure of this information should entail.

Among thematic indicators, analysts assessed two related to informing and engaging specific population groups — defenders and internally displaced persons. The program defined several priority topics that must be consolidated on accessible, well-structured pages. For defenders, these topics include rehabilitation, professional reintegration, financial support, assistance for family members, and available benefits.

Eight cities provided a dedicated resource with at least three of these components. Dnipro, Zaporizhzhia, and Kharkiv organized this content in the form of a guide, which is a user-friendly approach. In contrast, Poltava, Lutsk, and Kropyvnytskyi did not meet the requirements of this indicator: in Lutsk, the city-council website and the website of the Social Policy Department contain separate, equally weighted pages for defenders that are not cross-linked — contradicting the single-entry-point principle; in Kropyvnytskyi, relevant information is posted as news items, making it significantly harder to locate.

For IDP pages, analysts looked for information on housing, employment, services, humanitarian aid, and the work of the IDP Council. Seven cities provided all or most of this information in a structured format. Dnipro, Zaporizhzhia, Poltava, and Kharkiv received no points: in Dnipro and Zaporizhzhia the information was scattered across several parallel pages, while in Kharkiv only ungrouped announcements for IDPs were published.

Key findings and recommendations

Viewing openness through the lens of European benchmarks highlighted the issue of formalistic approaches taken by local self-government bodies in publishing information. Cities that provided superficial or literal compliance with legal requirements and program recommendations were less likely to achieve high scores in the assessment of openness and public engagement. Program analysts placed themselves in the position of a resident interested in the work of their city council or seeking specific information, but without the time, resources, or skills to sift through all public communications of the council or mayor.

The analysis revealed several key problems in municipal practices. First, the organization of official web resources of local self-government bodies is often inadequate. The “single entry point” principle is applied inconsistently, and significant gaps persist in the structuring of essential information.

Second, despite the conditions of full-scale war, many cities continue to manage humanitarian aid in a fragmented manner. Communications on aid received and distributed by city councils remain unstructured and difficult to locate. This situation complicates coordination between authorities, residents, and partners, reducing the overall effectiveness of assistance.

Finally, all of the above issues related to citizen-oriented openness have a direct impact on the social sphere. Untimely and non-transparent communication complicates access to critically important information and services for internally displaced persons, defenders and their families, low-income households, and other vulnerable population groups.

The program recommends that all cities (not only those included in the pilot study) take the analytical findings into account and revise their approaches to resident engagement by:

- Reviewing the organization of the official city council website and key specialized web resources. Optimize the structure of web platforms and ensure the presence of dedicated sections/pages on key topics where all relevant documents, links, and communications are consolidated in a format that is logical and user-friendly.

- Placing greater emphasis on transparent disclosure of information on humanitarian-aid management. Ensure the presence of a dedicated section or page on the city council website that provides up-to-date information on humanitarian aid, available programs, procedures for receiving assistance, reports on resource distribution, and information about responsible departments. The information must be presented in an accessible format and updated regularly.

- Communicating in a timely, clear, and accessible manner with internally displaced persons, defenders, citizens requiring material support due to Russian aggression, and other vulnerable groups.

- Ensuring consistent publication of the full information cycle on the work of the council. Maintain structured archives for all elements — from announcements to minutes — for sessions of the city council, the executive committee, and standing committees. These elements should be interlinked logically and published within the required deadlines (announcements must include a preliminary agenda and a link to the livestream; livestreams or video recordings must be published no later than the day after the meeting; video titles must correspond to the meeting number and date; minutes and adopted decisions must be published on time with recorded voting results).

- Reviewing the performance of search tools. Ensure that users can quickly locate information across documents, news, and other sections using keyword searches and logical filtering options.

Testing city councils for compliance with European standards in openness and public engagement is the first step in assessing a city’s ability to be both human-centered and community-centered. These skills — navigational logic, clear structures, and rapid access to essential, high-quality information — will form the foundation for subsequent research.

The program will prepare tailored recommendations for each city council included in the study, which will serve as roadmaps for improving the real openness of local self-government bodies toward citizens. The indicator-by-indicator results for each city are available at the link.

This research was prepared within the framework of the program on institutional development of Transparency International Ukraine, which is carried out with the financial support of Sweden, as well as with the support of the MATRA program of the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Ukraine.

Transparency International Ukraine is an accredited representative of Global Transparency International. Since 2012, TI Ukraine has been helping Ukraine grow stronger. The organization takes a comprehensive approach to the development and implementation of changes for reduction of corruption levels in certain areas.

TI Ukraine launched the Transparent Cities program in 2017. Its goal is to foster constructive and meaningful dialogue between citizens, local authorities, and the government to promote high-quality municipal governance, urban development, and effective reconstruction. In 2017–2022, the program annually compiled the Transparency Ranking of the 100 largest cities in Ukraine. After the full-scale invasion, the program conducted two adapted assessments on the state of municipal transparency during wartime. In 2024, the program compiled the Transparency Ranking of 100 Cities, and in 2025, it launched an updated format for assessing city councils — the European City Index.